CULTURAL DEMOCRACY AND REPRESENTATION

by Kyoung H. Park

As a gay, Korean playwright born and raised in Santiago, Chile, I take part in our theater community as an outsider—foreign born and constantly struggling with immigration issues—and I understand that both my inclusion and exclusion in the field is part of a larger cultural discourse about America’s ever-changing society. My personal learning curve to become part of this community has been steep, but it’s my privilege to be part of the conversation and I take this privilege seriously, as I am often asked to “represent” the communities I am identified with. Whether I speak about being Korean, the censored history of Pinochet’s regime in Chile, the struggle for gay rights, or the challenges of being an immigrant, I address these issues within an American context, where race relations and institutionalized systems of cultural production and cultural oppression permeate into our institutions and affect the lives of minority artists and the perception of our work.

I joined the Brooklyn Commune when I saw a need for leadership in the Commune’s Diversity and Inclusion Team. During our Commune’s latest meeting, held at the Invisible Dog Center on May 12th, a group of artists and arts managers held a conversation to identify the barriers to diversify their respective practices and organizations, concluding that the primary challenge is economic, for both artists and audiences.

In cases in which diversity was being addressed with some success, we were still critical of minority representation being addressed through token artists or projects, and the need to raise the visibility of our community’s inherent diversity through inclusive social practices, such as community-based, educational programming, the practice of alternative economic models to support artists, and the engagement in movements for social justice in which live and digital communities are provided greater access to the performing arts.

We asked ourselves the perennial questions:

- How can we diversify audiences, work, and artistic leadership?

- How do we address the value of diversity in artistic programming?

- How do we become socially responsible and address racism, ageism, sexism, or other types of ableism?

The group recognizes that there is a lot of work to be done, and is committed to open a line of dialogue with the community to research and critically examine how we can diversify not only our creative work, but the way we engage with communities, and support new artistic leadership that will take race and gender into account. We are slowly building a framework to further our research and maintain our process transparent, to continuously share discoveries and information which may be old to some constituents, but new to others.

While the participation of minority artists and audiences goes hand in hand, we are now focusing our attention in the experience of minority artists in the performing arts, while we design a larger survey to research the participation of diverse audiences in cultural institutions. As we are a small research team, our work begins with simple questions with interesting data and articles we have found, to open the forum to all of you who may have relevant information, documentation, and questions about this matter. This topic will be an on-going topic through the rest of our research, and the primary topic of discussion for the Brooklyn Commune’s Cultural Democracy and Representation Team, which will meet at the Invisible Dog Center on July 14th.

The goal of our team is to address the systemic problems within our institutions in terms of race, class, gender, dis/ability, faith, age, and through this research, make a change. To that affect, we are enlarging the scope of our research to discuss Cultural Democracy and Representation in the Performing Arts. Culture is what guides our understanding of our identities and artists engage our communities to further our culture; yet, within our cultural institutions both artists and audiences need to be engaged in a larger conversation of who we are as a multi-cultural society comprised of varying cultural paradigms.

This is when the democratization of culture needs to be addressed, to discuss issues of just and equal participation in the arts, through the enhanced financial support of diverse artists and communities to not only “re-present” the plurality of our cultures, but to humanize our experiences while critically examining the cultural policies that affect us economically and politically, as these factors ultimately determine who we are as a community of artists and the impact of our work.

(MIS)REPRESENTATION and PARTICIPATION of MINORITY ARTISTS in the PERFORMING ARTS

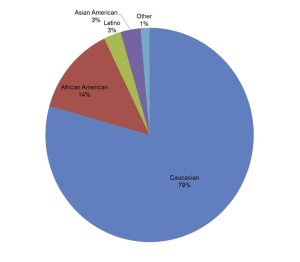

For two years, the Asian-American Performers Action Coalition has surveyed the Ethnic Make Up of Casts from Broadway and Non Profit Theaters in New York City. Their latest results show that during the past 6 years, the representation of actors has been: 79% Caucasian, 14% African-American, 3% Latino, 3% Asian-American, and 1% Other.

In 2011, the Pew Research Center’s Census Bureau reported the US Population as 63% Caucasian, 12% African-American, 17% Latino, and 5% Asian-American and projected the growth of African-American, Latino, and Asian-American communities and the decrease of Caucasian (White) Americans.

While analyzing these numbers 1-1 could provide us a rather simplistic understanding of which race is over and/or under-represented on our stages, we must also consider the limitations of data analysis. Neither of these statistics take into account gender, age, dis/ability, and/or sexuality. It is also interesting to note the omission of other minorities such as Arab Americans. Furthermore, a racial label such as “Latino” is comprised of a rich, diverse community of individuals with much more nuanced histories and constituencies, so each race and the discussion of race needs to be addressed with far more cultural sensitivity.

Having noted these limitations, these numbers make me think of some conclusions drawn during our latest Brooklyn Commune meeting. The demographic shifts in this country are evident, but while some institutions have decided to nurture a new generation of artists to prepare for this change, there is still much work to be done to address current practices.

We are not in a “post-racial” world, but rather in a society in which a growing number of minorities require us to expand our notions of diversity and improve our practices to be more socially inclusive, engaging in the complexities of America’s social fabric rather than making diversity an “institutional trend” that will result in cosmetic changes in artistic programming and/or enhanced marketing strategies with no real engagement with our communities.

Diane Ragsdale has criticized how supporting the diversification of institutions needs much more than coercive support from the funding community, as the management of these shifts requires long-term support of organizations to truly make a change. However, Doug Borwick argues that we need to question who is leading this change, how investments are being made, and how we acknowledge the racial hierarchies of artists, arts managers, artistic leaders, and funders in the process of creating a multiracial “we” which is inclusive of gender, sexual, and class formations.

A failure to diversify artistic programming without the proper inclusion and participation of the artists we seek to reach out to, can lead to problems. The most loudly heard offenses these days are the casting controversies taking place around new American plays. Whether it is Bruce Norris condemning blackface in a German production of his play “Claybourne Park,” Stephen Adly Guirgis reprimanding the casting of a regional production of his play “Motherf**ker with the Hat,” or the increasing number of yellowface, brownface, and orangeface to represent Asian-American characters, it is clear that we should not only include minority actors on-stage, but address the inherent cultural insensitivities that allow us to look-away when black/yellow/brown/orangeface and white-washing is taking place in the casting and creative process. Unless these current artistic practices are changed, theaters may unknowingly reinforce the problems we seek to address when we speak of “diversity.”

To take this issue one step further, Borwick reflects on his understanding of the White Racial Frame and how it intersects with cultural policies and cultural practices. This frame is described as a “foundational frame from which a substantial majority of white Americans—as well as others seeking to conform to white norms—view our highly racialized society.”

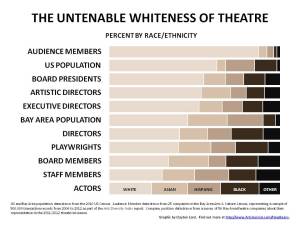

To address the lack of racial diversity in the performing arts we need to not only examine the economic factors limiting the participation of minority artists and audiences, but address issues of access, legitimacy, and power, and how these are affected by white privilege in the field. For those who do not see whiteness as an issue, consider last year’s season at the Guthrie Theater, which was heavily criticized for being predominantly white and male, and this year Arts Diversity Index for 56 Bay Area theater companies, by Clayton Lord, which outlines the “Untenable Whiteness of Theatre.”

In a recent article for HowlRound, Rebecca Stevens asked whether the American Theater had the same problems as the GOP. Discussions of diversity can lead white institutions to talk and talk while receiving money and attention for their discussions, without necessarily changing, So, as Stevens asks, how do we take responsibility for the theater and help it survive and change for the better? If the theater was like the GOP, how do we become responsible for the theater rather than shaming and blaming the institution?

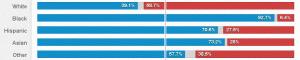

Perhaps, the success of the Democratic Party in the last Presidential elections has something to teach us. If we were to consider the participation of artists and audiences in the theater a cultural right which is granted to all Americans equally, perhaps the racial constitution of our theater would be more reflective of the participation of minorities and people of color in our democracy.

In the Comment Section below, or in our Brooklyn Commune’s Facebook page, please take a moment to tell us your experiences and thoughts as a minority artist, and let us know what challenges and opportunities you face in the Performing Arts. We are curious to hear the stories of artist and arts managers, and please do share with us your thoughts on how we can support the plurality of our cultures and identities and make that the focus of our cultural institutions.

Discussion

No comments yet.